In part 1, we discussed how beliefs are formed (i.e. epistemology) and defined various types of evidence. Our next installment will cover logical fallacies and cognitive biases that often influence our perception of reality and decision making.

Logical Fallacies

There are A LOT of cognitive biases (188 recorded – see HERE) and various fallacies and thoughts on fallacies (which can be read about HERE). We will cover just a few pertinent items related to clinical practice.

Confirmation Bias – seeking out information which confirms your prior held beliefs without consideration of the validity of the information. I typically call this the “Google effect”. If, as a chiropractor, I believe joint manipulations are effective due to my schooling and wanted to search for information about it – we can find many websites confirming my prior held belief that they are effective and should be used as an intervention. Further complicating the issue is that we can find published research claiming the effectiveness of joint manipulations – we will discuss the quality of evidence later.

Cognitive Dissonance & Motivated Reasoning – think of cognitive dissonance as the discomfort and response to simultaneously holding two beliefs that are in opposition of one another. Back to the Google example: what happens when we find a google link that appears to contradict our prior held belief? There’s a good chance this leads to motivated reasoning to sustain inconsistent beliefs about a particular topic, or rationalization of prior belief in spite of the new evidence. For example: many of us are aware of the benefits of physical activity, and yet we rationalize why we do not engage in regular physical activity (lack of time, overworked, no opportunities, etc). Overall, motivated reasoning can be thought of as a coping mechanism when recognizing cognitive dissonance – or as the opening image to this piece alludes to – “I want to believe.”

Post Hoc ergo Propter Hoc Reasoning – also known as a causation fallacy and translates to “after this, therefore because of this”. This is a fallacy of temporality, meaning when one event (B) occurs after another event (A), we erroneously assign causation between the two (“A caused B”). Some context to this fallacy will help with understanding.

I originally learned about this fallacy in an undergraduate criminology class. The example presented was seeking to better understand why murder rates were spiking during the summer. While on the search for related variables, the investigators noticed ice cream sales also spike during the summer. Ipso facto, ice cream causes murders. This may be silly but drives home the point regarding this example of fallacious thinking when it comes to establishing causality. Some other examples can be found HERE.

For the clinical context we can think about the spurious correlations we draw from interventions Often we tend to think we have a greater effect on the patient and situation than is the case. Enter the primary argument for utilizing quality studies that are designed in an appropriate way to answer the clinical question at hand. As previously mentioned, hopefully these studies can reasonably control for potential confounders or secondary factors influencing intervention effectiveness (examples being placebo and nocebo effects related to expectations, conditioning, Hawthorne effect – to name a few, see Hartman 2009 & Testa 2016).

Research may be rationalized based on clinical (aka collective) equipoise,”…defined as the genuine uncertainty within the scientific and medical community as to which of two interventions is clinically superior.” Master 2014 The primary goal being advancement of scientific knowledge about the efficacy of a particular intervention to generalize into clinical practice with individual patients. Although the concept of clinical equipoise isn’t without complaints, especially related to RCTs, there also exists another type known as individual equipoise. Miller et al discuss individual equipoise in a research context as “….physician-investigators must be indifferent to the therapeutic value of the experimental and control treatments evaluated in the trial.” Miller 2003

In research, investigators need to ensure personal equipoise among experimenters consulting with or delivering interventions to involved participants to minimize biasing outcomes. However, in clinical practice this is unlikely, as Cook and Sheats outline with the topic of manual therapy, “Given that ‘clinician experience’ is a form of ‘evidence’, preconceived personal preferences associated with an intervention, whether wrong or right, are likely always present. Consequently, it is arguable whether an environment can exist in a complete state of equipoise, especially when manual therapy is the treatment intervention.” Cook 2011 Controlling for clinician preferences is likely quite difficult in a real world clinical setting. Our bias as clinicians will show through and influence decision making as well as intervention effects. This is more reason to follow what the totality of research evidence shows about a particular intervention in order to minimize the effect of our underlying biases. With that said, there is a case for enhancing placebo-like contextual effects in an ethical manner (See Testa above as well as – Peerdeman 2016 & Peerdeman 2017).

Appeal to antiquity – an assumption that the age of an idea implies greater validity or “truth”. We see this claim often with interventions such as cupping or acupuncture/dry needling and other Traditional Chinese Medicine interventions.

Appeal to novelty – in opposition to number four above, appeal to novelty assumes the newest, “latest and greatest” idea or intervention must be better than the older approaches, and therefore has greater efficacy. Often, this is where we hear clinicians claiming that their practice is ahead of the research base, when in reality the research is more often debunking clinicians’ claims while taking about 17 years to be adopted in practice. Recent interventions that come to mind include platelet-rich plasma Injections, stem cell injections, or — more relatable to my own experience — fMRI being “the answer” to peering beneath the surface of humans.

Argumentum Ad Populum & Appeal to Authority – these two tend to go hand in hand in today’s world of social media. Appeal to authority implies a perceived position of authority necessarily espouses “Truth” – for example, someone with the title of “Doctor”. Another example might be someone with an arbitrary number of followers, let’s say 100,000 on Instagram, or perhaps a celebrity with a lot of social “clout”. These prior examples are representative of appeals to popularity – because an idea or person becomes popular, therefore popularity implies efficacy or “Truth”. We also tend to see the phenomenon of promiscuous expertise occur with popularity as well, where popularity or authority results in people becoming emboldened to venture outside their areas of expertise.

Red Herring Fallacy – A red herring is considered something that is misleading and/or a distraction from a relevant question and often leads to false conclusions. In the world of healthcare, this can be akin to incidentalomas, which originated as a term from finding asymptomatic, incidentally-found tumors. The term can be broadly applied to many findings from radiologic imaging or other investigative tools that are identifiable in asymptomatic populations, have low correlation to symptom development, and self-resolve or do not progress to cause any detrimental effects. This means management and prognosis ultimately do not need to change. Unfortunately, finding an incidentaloma on imaging can lead to what has been termed “VOMIT”: Victims of Modern Imaging Technologies. These imaging findings cause unnecessary worry by clinician and patient, leading to increased downstream testing (healthcare utilization) and thus increased health costs – with real potential of having detrimental effects on the patient. Hayward 2003

Much of this discussion comes down to attempting to answer the clinical question – How can I best help this person? Answering this question is directed by the lens through which we view the patient (e.g., biomedical vs biopsychosocial). Often we are led astray by red herrings because we’ve not examined what research evidence is showing us about the relevance of a particular finding in the context of the patient’s case. As an example, we can frame this discussion in the context of low back pain, examples include spinal “degenerative disc disease” (i.e. normative age-related changes/adaptations), lumbar disc herniations, modic changes, lumbar spinal stenosis, spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, Schmorl nodes, scoliosis — the list goes on — as we approach a complex phenomenon such as pain from a overly biomedical reductionist view. Yes, some or all of these findings may be present, but how much they actually matter for the person’s current situation and future prognosis is a different discussion. This further validates the need for quality research evidence. In this context, for identifying a supposed problem, we need long-term observational prospective studies to figure out risk factors, correlation to symptoms, and label something as a problem needing intervention – leading to our last discussion point in this section.

False Dichotomy Fallacy (false dilemma) – for our context this is proposing two categories as the only options (either/or). For our low back pain discussion, this would mean framing imaging findings as problems or not problems, injuries vs not injuries, abnormalities vs normalities. Instead of examining findings in this context, we would likely be better served to frame this discussion through a spectrum. However, the inherent issue here is the individual human. Where one individual falls on the spectrum of findings and crosses into imaging findings necessitating alternative management (e.g., “conservative” vs. surgical) is a bit muddier in many non-traumatic situations. Instead we are relegated to addressing the individual by applying current evidence on their situation, generalizing external evidentiary findings as best as possible. This likely explains why we can have the same findings in an asymptomatic population versus symptomatic (I realize the irony of creating dichotomous categories of asymptomatic vs. symptomatic and this is actually a major research question ongoing in various contexts like low back pain with identifying when someone is truly “symptom-free” or having an initial case of acute low back pain). Ultimately, this leaves us trying to identify when something necessitates a particular intervention, or perhaps we can think of this as a continuum of interventions (education → activity modification → medications → surgeries; but these don’t have to be mutually exclusive, and can occur simultaneously).

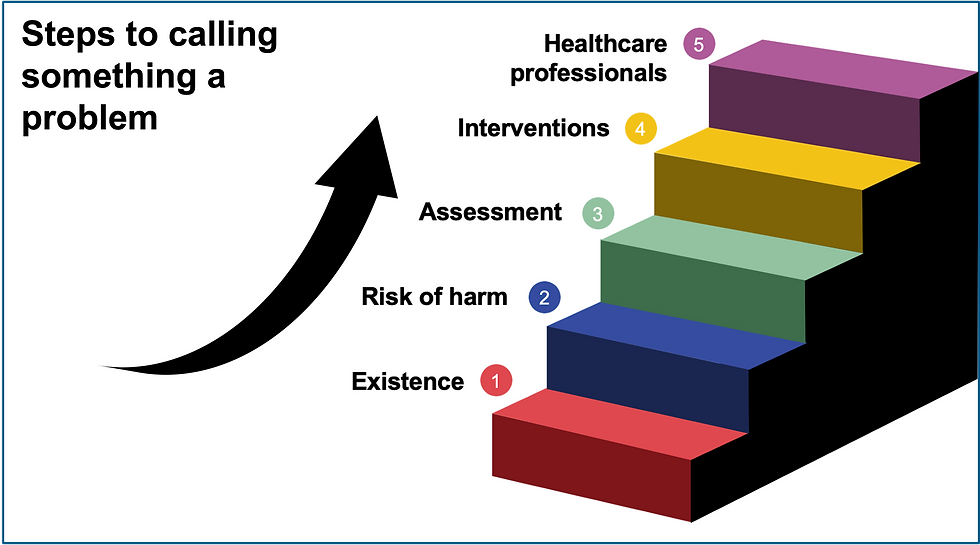

Let’s discuss this through the lens of vertebral subluxations in the chiropractic world. In order to assert that vertebral subluxations (VS) exist and necessitate a particular intervention, we first need to use science as a method to assess such a belief.

Step 1 – We need evidence demonstrating VS exist, a prevalence rate identified in asymptomatic and symptomatic populations. Base rates of a finding helps us identify correlation to symptoms. Saying everyone has a VS nullifies this from being a problem and instead it is a normal part of being a human.

Step 2 – Once evidence has been identified demonstrating VS existence, then we need evidence demonstrating there’s a risk to having them. They’ve been demonstrated to have a non-negligible detrimental harm to those they are identified in and if not addressed may affect prognosis, quality of life, function, etc.

Step 3 – We need valid assessment tools for identifying VS (reliable, accurate, and replicated from clinician to clinician).

Step 4 – Upon identifying the existence of VS (thoeretically), demonstrating that they confer a risk to the individuals presenting with the finding (theoretically), we now need to identify interventions to address VS in a meaningful manner (prognosis, quality of life, function, life span, etc.). Here we need to have a conversation of efficacy and weighting risk vs benefits for the proposed intervention compared to not intervening. Meaning, have the interventions been demonstrated to have meaningful effects beyond placebo/contextual meaning effects while addressing VS that doesn’t then bring more risk than leaving VS alone, while also considering patient context and preferences.

Step 5 – We then must identify clinicians adequately trained and prepared to help individuals with VS in the healthcare system.

If the reader has heard of Bayesian inference or decision-making, this process may sound familiar. Since the push for evidence based practice, there’s also been advocacy for the uptake of Bayesian statistics, which can be read more about HERE.

Overall, these are a few examples of biases and fallacious reasoning that science as a method attempts to overcome. The methodology is beneficial for healthcare to further our understanding about pathology and interventions. However, we must recognize shortcomings of science as a method, specifically in the healthcare context, over-weighting information based on calculative, physical body objectification to understand the human experience. Although this isn’t the point of this overall article, I would be remiss to not state that we must strive to find balance between using science as a method for healthcare while recognizing the type of questions science is bound to and the information we can garner, being cautious of slipping into scientism. There are strong arguments for expanding beyond just calculative thinking and layering in meditative/reflective thinking (see Afflicted by Nicole Piemonte, PhD). Our final section will discuss evidence based practice further.

Stay tuned!

Key Takeaways:

Humans are prone to cognitive biases that lead to fallacious reasoning.

We cannot always prevent flaws in our thinking, but being aware of these issues may mitigate their prevalence.

Science as a method remains one of our best tools for moving closer to “Truth” while minimizing flawed reasoning.

References:

Hartman SE. Why do ineffective treatments seem helpful? A brief review Chiropr Man Therap. 2009; 17(1).

Testa M, Rossettini G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: How contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes Manual Therapy. 2016; 24:65-74.

Master, Zubin & Smith, Elise. (2014). Ethical Practice of Research Involving Humans. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.00178-1.

Miller FG, Brody H. A critique of clinical equipoise. Therapeutic misconception in the ethics of clinical trials. Hastings Cent Rep. 2003; 33(3):19-28.

Cook C, Sheets C. Clinical equipoise and personal equipoise: two necessary ingredients for reducing bias in manual therapy trials Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2014; 19(1):55-57.

Peerdeman KJ, van Laarhoven AI, Keij SM, et al. Relieving patientsʼ pain with expectation interventions PAIN. 2016; 157(6):1179-1191.

Peerdeman K, van Laarhoven A, Bartels D, Peters M, Evers A. Placebo-like analgesia via response imagery Eur J Pain. 2017; 21(8):1366-1377.

Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research J R Soc Med. 2011; 104(12):510-520.

Botvinik-Nezer, R., Holzmeister, F., Camerer, C.F. et al. Variability in the analysis of a single neuroimaging dataset by many teams. Nature (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2314-9

Chojniak R. Incidentalomas: managing risks. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(4):IX‐X. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2015.48.4e3

Hayward R. VOMIT (victims of modern imaging technology)–an acronym for our times BMJ. 2003; 326(7401):1273-1273.

Ashby D, Smith AFM. Evidence-based medicine as Bayesian decision-making Statist. Med.. 2000; 19(23):3291-3305.

Malloy D, Martin R, Hadjistavropoulos T, et al. Discourse on medicine: meditative and calculative approaches to ethics from an international perspective Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2014; 9(1):18-.

Comentarios